I just finished teaching an Introduction to Film class to a group of students at the University of Pittsburgh who mostly watch “content” on their phones. At the outset, for some— who have come of age with the pandemic and Tik Tok— the idea of watching a two-hour movie in a classroom was something they had to endure rather than enjoy and there were challenges trying to connect with them. During this past semester, I thought a lot about a professor I had as an undergraduate at Duke University who gave me my own education in film. My pathway to teaching was somewhat serendipitous having spent the first half of my professional life writing movies and TV shows in Los Angeles. But I might note have had either of these careers were it not for a brilliant, charismatic, and caring professor David L. Paletz who changed my life in a way that sounds like something out of a Hollywood movie.

Like many of my students, (and Dukees in the 80s), I had started off pre-med as I bounced through various majors— Bio, Psych, English, Poli-Sci, History— with no real sense of what my future might be. As a psychological trick to keep my grades up, I vowed if my GPA slipped below a certain point, I would jump out of a plane. Paletz taught a notoriously challenging yearlong “Politics and The Media” class in which he showed some of the films I now screen for my students. With an infamous 35-page syllabus and Paletz’s reputation for being a hard grader who almost never gave an “A,” enrolling in PS 153/154 seemed the academic equivalent of skydiving.

Professor David Paletz was an enigmatic English man with a pension for black turtlenecks and a mysterious aura about him. There were rumors that in his younger days, he and his wife Darcy had lived in Los Angeles and hung out with Lenny Bruce. Like many things Paletz, this remained speculation, as the professor himself rarely disclosed such things. The class met once a week from “6:30 p.m. to 11 or later” and its stated purpose was “to explore, analyze, and illuminate many of the relationships between authority and the media of mass communications.”

Technically Paletz was in the Political Science department, but when he started teaching in the 1960s, he was one of the first to employ using films as a teaching tool. Part of that was the technical challenges. Unfathomable to my students who scoff when I can’t operate the DVD player, to show us a movie, Paletz had to bring cans of films in the classroom— sometime from his own person collection— and run them through a projector. In terms of politics and the media, he was pioneering the field as there were few in academia taking that subject seriously. Much of Paletz’s own theories would later emerge in his seminal book “Media Power Politics” which established him as a leading scholar in the field and is still being used today.

I should note I was hardly the only one whose life Paletz had profoundly influenced, as his former students include members of Congress, an Olympian, a University President, a network anchor (CNN and PBS’ Judy Woodruff), and my best friend Rob Cohen, now a prominent entertainment attorney who recalls the films which Paletz showed us as being what he remembers most from his Duke education. Our mutual friend Lori Levinson (Paletz’s class created lifelong bonds) recently described Paletz as “prescient.” He showed us how politicians used media like Richard Nixon’s “Checkers” speech in the 1950s when he defended himself against accusation of improperly using a secret political funds by talking about his cocker spaniel named “Checkers” and Robert Drew’s 1960 documentary Primary where we saw how charismatic JFK was on camera. And of course, we were going to school in the 80s when a B-movie actor named Ronald Reagan was in The White House and Paletz’s class foresaw the day a reality TV star would end up in the White House.

The Intro To Film class I just taught fulfills a Gen Ed requirement, and some hear the word “film” and think that implies what we called “a cake class” one can just breeze through. To disabuse students in his class of any such notion, the first day Paletz pointed out the voluminous required readings assignments including Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan on the uses and abuses of speech; Max Weber’s The Theory of Social and Economic Organization and Milgram writing on his provocative experiments so we could understand individuals blind obedience to authority; reading J.S. Mills “On Liberty” and contrast that with Rousseau’s argument for the restriction of freedom of speech. And there was the “recommended reading” each week which listed a dozen or so more works Paletz thought it advisable for us to be familiar with.

The films Paletz showed were as varied as the readings. There was Marx’ Brother’s subversive Duck Soup where Groucho Marx’s Rufus T. Firefly ruling over Fredonia as a comically-inept, strong man-style leader in ways which might remind some of our current administration. And Eisenstein’s Strike for which he had us read The Grand Inquisitor section from F. Dostoevsky’s The Brothers’ Karamazov and V.I. Lenin’s “What is To be Done?” For the section on Nazi Germany, Paletz’s screened Triumph of the Will in which Leni Riefenstahl used her considerable skills as an artist to aid Hitler rise to power. The film opened with a shot of The Fuhrer descending from the clouds to Wagner and then she used the low angles of him giving him full authority as he spoke to the adoring crowds during massive Nazi rallies. Paletz had us read an interview with Riefenstahl she did after the war where she denied being a propagandist claiming she only had “boots” to work with.

He showed us Marcel Ophuls’ Sorrow and The Pity, a four-hour opus on Vichy France’s collaboration with the Nazis Woody Allen kept dragging Diane Keaton to in Annie Hall and Alain Resnais’ Night and Fog, juxtaposing tranquil, color footage of abandoned concentration camps after the war with the black-and-white archival images of the atrocities. There were whispers as a young boy, during The Blitz in WWII, Paletz had been evacuated with his mother to the English countryside , but the professor never let on his personal background or his ideological leanings.

Like de Tocqueville, Paletz looked at America through the eye of an outsider, and he seemed bemused by what our movies revealed about how we saw ourselves. He showed us Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes To Washington where an idealistic Jimmy Stewart saves The Senate from its evil ways (at least temporarily), but noted the number of at times Abraham Lincoln was shown in the film, as if to signal that in the end, America was a decent country that morally did the right thing.

Paletz’s lectures were infused with his droll British wit, and he even infused a few “catch phrases” such as “it all fits.” On might question why were we watching Buster Keaton in a Politics and Media class and hearing how he came from a background as a child performer in his family’s Vaudeville act in which he was thrown across the stage? And how the magician Harry Houdini gave Keaton his nickname when as a toddler Joe Keaton Jr. fell down a flight of steps and Harry said to his parents, “that’s some Buster you have there.” Ostensibly, we watched Cops, a Keaton two-reeler, as part of a section on “Police and Authority” paired with Frederick Wiseman’s documentary Law and Order on the Kansas Police Department. In it, Keaton plays a hardworking, innocent everyman who is wrongfully accused of misdeeds and chased across Los Angeles by the entire police department. What did that tell us about Keaton’s view of authority and law enforcement in society? Paletz asserted that Keaton was the true genius of the silent era who got overlooked becuse of Chaplin got all the attention. He showed us Sherlock Jr. where Buster is a movie projectionist who longs to be a successful detective and solve a crime to impress a girl where Keaton climbs out of his body and onto the screen, a pioneering use of “double exposure.” As with all his films, Keaton did all his own stunts, including riding on the handlebars of a motorcycle traveling at high speeds and traveling alongside a freight train when he pulls a rope to a water tower and is thrown down to the steel rail by an avalanche of water. Keaton had a blinding headache after doing that stunt, but went back to work, but it wasn’t until 11 years later that he discovered the had a broken neck. It all went back to the vaudeville act. You see, “it all fits,” Paletz would remind us.

Another of Paletz’s runner I recall is “things in life and in movies are not always as they appear. “ The Manchurian Candidate directed by John Frankenheimer is about a plot to kill a candidate for President. In the movie, we are lead to believe it is the Chinese communists who are subverting America through a brainwashing program, but that turns out to be a false flag for the right-wing conspiracy folks who are actual behind everything. Paletz informed us how Angela Landsbury who played the brainwashed assassin Raymond’s mother was only a few years older at 37 than her “son” actor Lawrence Harvey. Then there was the accepted lore of how the film had been removed from theaters by Frank Sinatra after the Kennedy assassination as Frank was close to Kennedy which was actually spread by a producer trying to drum up interest in the film after its disappointing box office when it was first released.

Paletz showed us Singin’ In The Rain, Gene Kelly’s musical comedy about the transition of movies from the silent to the sound era, noting how the actors in the film Don Lockwood and Cosmo Brown have subversive attitudes to the ineffectual studio head, and because Paletz felt it was important we have a sense of how movies were made. But we suspected Paletz showed because he loved the movie.

When I showed Singin’ In the Rain to my students this past semester, I of course mentioned how Gene Kelly was a Pitt alum who actually wanted to be a short stop for The Pirates before his mother made him take dance lessons. Channeling my best David Paletz, I also pointed out to them how while we see Debbie Reynold’s character Kathy Seldon dubbing the screechy silent film star Lina Lamont in the movie, in reality, Lina was played by Jean Hagen who had a trained singing voice and it was Debbie Reynolds who had some of her singing dubbed over in the film. “Things in life and in movies are not always as they appear.”

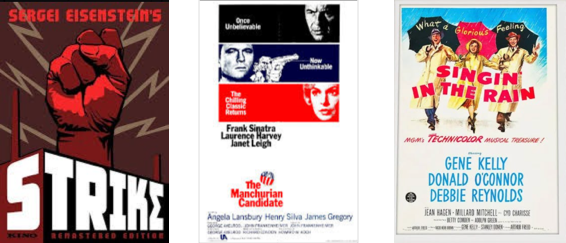

This Fall I had the surreal experience of teaching a film class while strangely St. Elmo’s Fire was back in theaters for its 40th anniversary. I usually tell people that the movie began as a short story I wrote my sophomore year in Professor Deborah Pope’s English class. But the truth is I would never have made it out to Hollywood or had a career in the film industry were it not for David Paletz and the final project I did for his Politics and the Media course.

Like everything else Paletz, the requirements for our final projects set a high bar which was supposed to reflect what we had learned in the course. The idea for mine came after the class where we were shown two separate films about quintuplets born in 1963 in Abeerdeen, South Dakota. The first was ABC News Reports the Fischer Quintuplets, an uplifting look at how the birth of these five new babies had been a blessing not just to this modest farm couple, but to the whole town of Abeerdeen. The second was a film Happy Mother’s Day where filmmakers Richard Leacock and Joyce Chopra let the events unfold cinema-verité style editing the footage to reveal that Mrs. Fisher was wary of the gifts the town was thrusting at the “happy couple” and Mr. Fisher was less than pleased at the year’s supply of milk for the babies as he was a dairy farmer who prided himself on self-reliance.

I was fascinated that the same subject matter could be edited so differently and pitched Paletz to allow me to film him giving a lecture and then let me edit the footage in several different ways. Paletz smiled wryly, and said it was a clever idea, but he did not care to be in the spotlight. Surely I could find another faculty member who might enjoy the attention.

I had taken a history class with Professor Lawrence Goodwyn, the author of “The Populist Moment” that told the story of insurgent Southern farmers after the Civil War who staged a nearly successful revolt against the Eastern banking establishment. Larry—as Goodwyn insisted we call him— had a Texan drawl and a mischievous Cheshire cat grin as he challenged us our first day as to why we were even in college. He accused us being the privileged sons and daughters of doctors, lawyers, and businessman with more possibilities than anyone before us in human history- and yet we were being processed like Velvetta Cheese through a system and would become… doctors, lawyers, and businessman. He asserted most of us would never have an original thought and would just accept “the received cultured.” He argued that while America called itself “progressive”, the distribution of wealth was getting worse and worse with the top 10 percent controlling 50th percent of the U.S. wealth. He encouraged us to wake up and take back our country and invited students to join him in the pub after class to discuss how we could create a true democracy.

When I approached Larry about the idea of filming his class, he referenced Todd Gitlin’s The Whole World Is Watching about how television shaped the New Left and anti-war movement and said that media was key to any revolution. He was in. Now I just needed to find access to equipment. Luckily Duke had a state-of-the=art student TV station and earlier that year, as I became more interested in media, I had contemplated doing a documentary, I had gone to a meeting at Cable 13. The President Laura Murdoch agreed to give me cameras in exchange for me agreeing to make a show for them. I produced a gameshow called The Roommate Game which was like The Newlywed Game with college roommates answering questions like “What sex life does your sex life most resemble?”

This gave me access to the station’s state-of-the-art 40 pound Porta-Pack which would allow me to film Goodwyn in his classroom. Now I just needed an accomplice in crime so I turned to my one friend at Duke, Rob Cohen, who wrote a satirically funny column Monday Monday which he published anonymously under his initials RMC. Rob would become the basis for the Andrew McCarthy’s sardonic Kevin character in St. Elmo’s Fire. Rob and I figured out the technical aspects of production and once the camera was on, Goodwyn proved a natural, pontificating to his engaged young comrades about how democracy (small d) was the street on which he lived.

At least that is how I edited it in the first version where Goodwyn looked like a benevolent democratic leader. Then there was a version where Goodwyn looked like a bombastic autocratic, and the students were intimidated. Using different reaction shots, I made a version where Larry seemed fascistic, but incompetent, and one where he was fair-minded, but students just ignored him. After hours in the editing room, I created four versions of Goodwyn as part of my film I called “Control.”

I was nervous as I screened the final project for Paletz and his class, bracing myself for his reaction. Paletz diplomatically said my experiment had failed on some level as no matter how I edited Goodwyn, he came across as a bit bombastic. What I had proven though, Paletz concluded, was the limitations of the medium, and, for that, he awarded me a rare “A minus.”

Around this time, there was a strange opportunity as for a Duke student to win a Duke/MCA-Universal Studios Scholar Award that came with $10,000 (at a time when Duke’s tuition was 6 K) and a ten-week internship with the head of film production at Universal. This had come about because Jake Phelps, the hippy-ish, Kurt Vonnegut look-a-like director of the Duke Student Union had protested in the early Seventies with a young kid Thom Mount. Thom had not gone to Duke, but lived in Durham, and had risen quickly in the entertainment industry becoming a baby mogul at 33, as the head of Universal’s film division. Jake had guilted Thom insisting that now that he as “The Man,” it was time to give back. Thom went to his boss Lew Wasserman, the owner of Universal, and pitched instead of just giving internships to kids at USC and UCLA, why not give a liberal art student from a place like Duke a chance.

The prize should have gone to Laura Murdoch, the Cable 13 President who was also a 4.0 student and edited the local TV news. I submitted my Paletz’s documentary “Control” and an essay about how I longed to make a movie about “my generation” that could inspire social change. Though Paletz was careful not to let on, I always sent he was an idealist, and his influence empowered me to believe that movies could make a difference in the world.

At this point, Paletz had become as much a mentor as a professor, and I had met with him multiple times during office hours which sometimes included going with him to his son Gabriel’s soccer practice, and at least one time, going over to his house on Happy Place where I met his wife Darcy who had an effervescence about her that seemed an interest blend with Paletz himself.

As for how I ended up winning the Duke/MCA-Universal Scholar Award, I don’t officially know, but later, I would hear that there was a cocktail party where the judges who were making the decisions were all mingling. Apparently, Darcy had worked with Laura at the TV station, and while acknowledging that Laura was very talented, having met both of us, suggested I might be a better fit for the culture in L.A. The judges ended up splitting the cash prize $5000 a piece and I got the 10-week internship. I felt guilty about this, but in the interview Laura gave to the Duke Chronicle she said how she didn’t real like Hollywood and was planning on going to Harvard Business School. (From what i can tell from Linked In, she has become a very successful tech exec in Northern California.)

I remember pulling up to the gates at Universal Studios that first day, peering past Scotty at the Universal security booth, and staring at the backlot which I had only seen in Singin’ In the Rain. Thom Mount had me sit in his office behind him observing as he took meetings as the President of Production at Universal. The first director who walked in the door was none other than John Frankheimer, the director of Manchurian Candidate which of course I had seen in Politics and Media. As Paletz had taught me, “it all fits.”

That first week I also met director Joel Schumacher, getting him “gazpacho, no croutons, no sour cream, and chopped egg on the side” for a lunch he was having with Thom. Joel was preparing to direct that biggest of all ‘80s stars, Mr. T, in a movie called D.C. Cab. A year later, I became Joel’s assistant and when D.C. Cab stalled at the box office, Joel read my screenplay St. Elmo’s Fire that I had adapted during my summer internship.

As usually only happens in the movies, less than a year later we were filming St. Elmo’s in D.C. with Rob Lowe, Demi Moore, Emilio Estevez, Andrew McCarthy, Judd Nelson, Ally Sheedy, Mare Winningham, and Andie MacDowell. As exciting as it was hanging out with those actors, one of my most vivid memories I have of the shoot was when Professor Paletz came to visit the set while we were filming in Georgetown. He was there with his son Gabriel and his daughter Susannah. Heartbreakingly, Darcy had passed away of cancer, but Susannah had that same smile and mop of curly brown hair of her mother. I recall their father explaining to him the basic information about how a movie is filmed. Perhaps it was not a coincidence that later Gabriel would become a film professor himself.

I would stay in touch with Professor Paletz throughout the years. (I still have trouble calling him David.) At one point, he was dating a journalist from The L.A. Times and we were having dinner at her high-rise apartment when the Rodney King riots broke out and suddenly we watching on television as behind us the city of Los Angeles was in flames. Talk about politics and the media.

When I accepted a serendipitous job offer to teach screenwriting and film at the University of Pittsburgh, I called up Paletz for tips (and begged for his syllabus.). He also had me talk to Gabriel who was teaching himself at that point. I got to know Susannah more when she got a job doing research at the University of Pittsburgh’s Learning and Research Development Center. The work was so complicated I could never fully understand it, but she had also not surprisingly worked with NASA. While living in Pittsburgh, Susannah had a daughter and I got to be there at the baby-naming watching Paletz as a new grandfather.

Paletz continued to look out for me, bringing me back to Duke to screen both St. Elmo’s Fire and My Tale of Two Cities, a documentary I made about Pittsburgh’s comeback story. Building on that first film I made for Paletz’s class, I have gone on to make documentaries on the Salk polio vaccine, transplant pioneer Dr. Tom Starzl, filmmaker George Romero, playwright August Wilson, and my own grandfather, a pioneer in the jukebox industry who founded the Cleveland Phonograph Merchant Association which a young attorney Robert F. Kennedy in the McClellan Hearings accused of being a front for the mob.

As I finished teaching this semester and asked students at the last class which films resonated with them, it was gratifying that quite a few said Singin’ In the Rain and was delighted when one even said Sherlock Jr. was now his favorite film. I was taken aback when a pre-med student handed me a beautifully wrapped present and a note saying to me how much the class meant to her, and thanking me for being an “uplifting” professor. I thought about David Paletz, who was that and so much more.

What I love about Sherlock Jr. is the Buster Keaton’s character literally escapes into the movies, and in so doing, he’s able to change— or believes he can— change the outcome of events. Paletz was right about Keaton being an under-appreciated genius and I know would balk at me saying so was he. He changed the way I see the world through the movies he showed me. But the lessons he taught us was more than just about film or politics, but about the human experience and for that, I am continually grateful and hope I pass a little of that on to my students.

I do wish Paletz had let me film his class so his lectures could have been shared with the world. Thankfully, Paletz’s wife Toril, a brilliant professor in her own right, has put together a website to preserve Paletz’s legacy. It has some of his writings, the movies he loved, tributes from the many students like myself whose lives were changed because of David. There is even some biographical informations and photos which demystifies the Paletz legend a bit, but also raise a few more questions. I’m sure as former students like myself peruse it further, we will discover that “it all fits.”